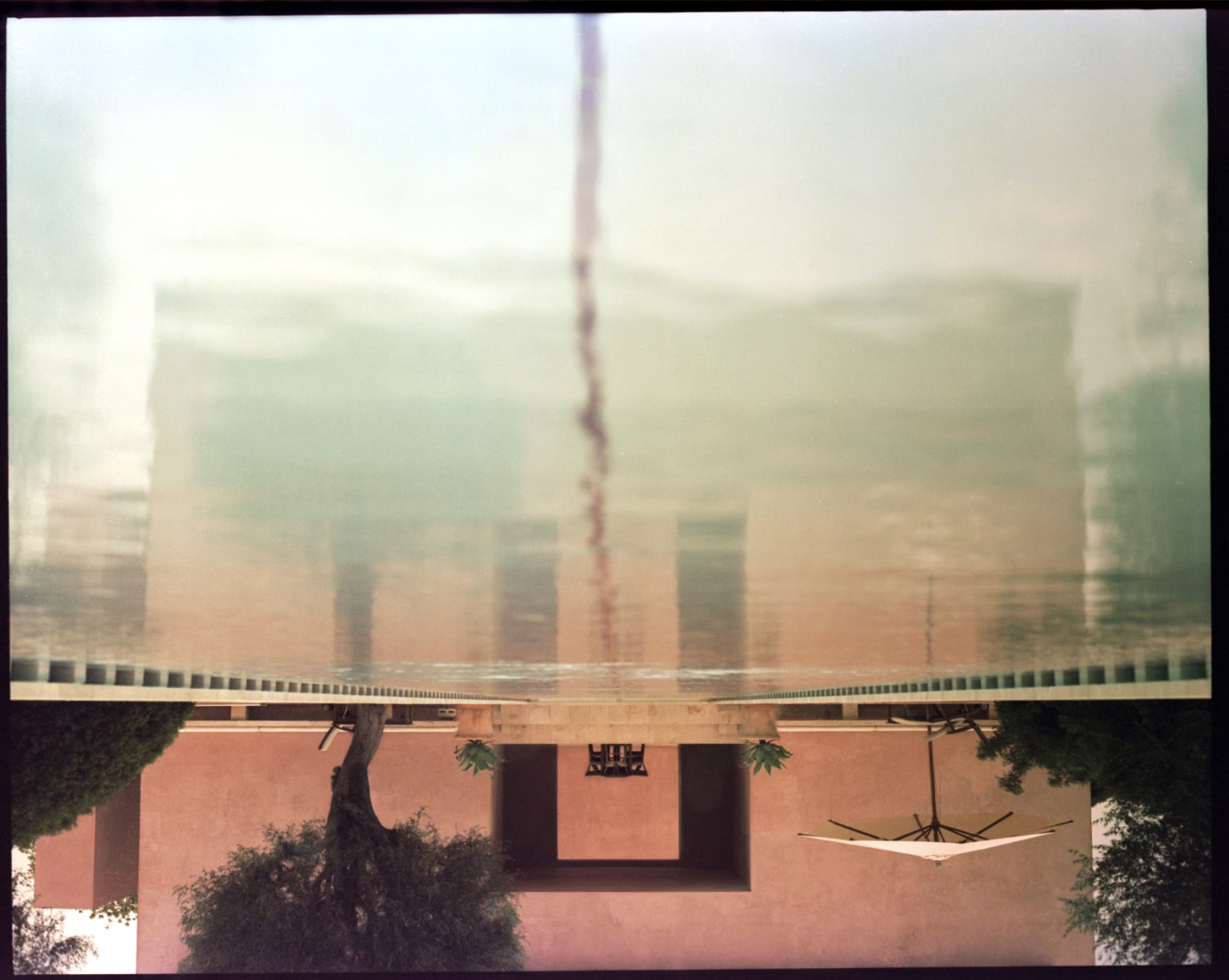

photographs by Josh White

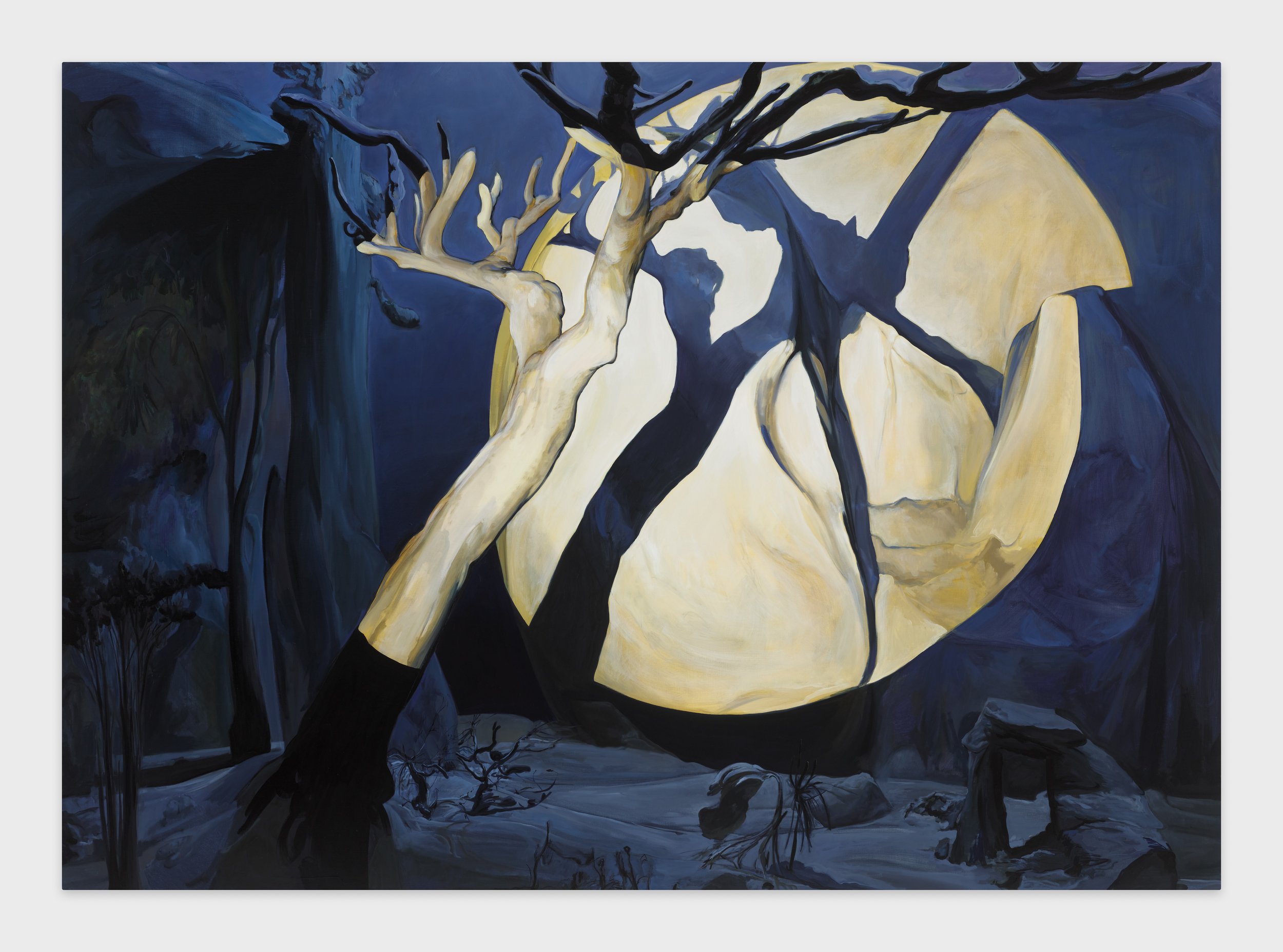

Between the minutia and the mirage of our fragmented contemporary existence, artists Darius Airo and Jon Plypchuk both create work imbued with a humorous and ironic darkness masked by playfulness. An inside joke, a half forgotten dream, a song lyric, abstracted figures caught between the waveforms of television static or the rain-drenched glass of a car windshield—our brains continually try to make sense of the world like an undecoded cypher. In Airo’s recent paintings and pastels, presented in the exhibition Mickey’s Mirror (opening May 25 at Abigail Ogilvy gallery in Los Angeles, curated by Josh White—whitebox.la), making sense of the world requires clever conceptual conceit of internal mirrors and the abstracted visages of iconic cartoon characters. In the following conversation, Airo and Plypchuk discuss how the world around them is absorbed into their work.

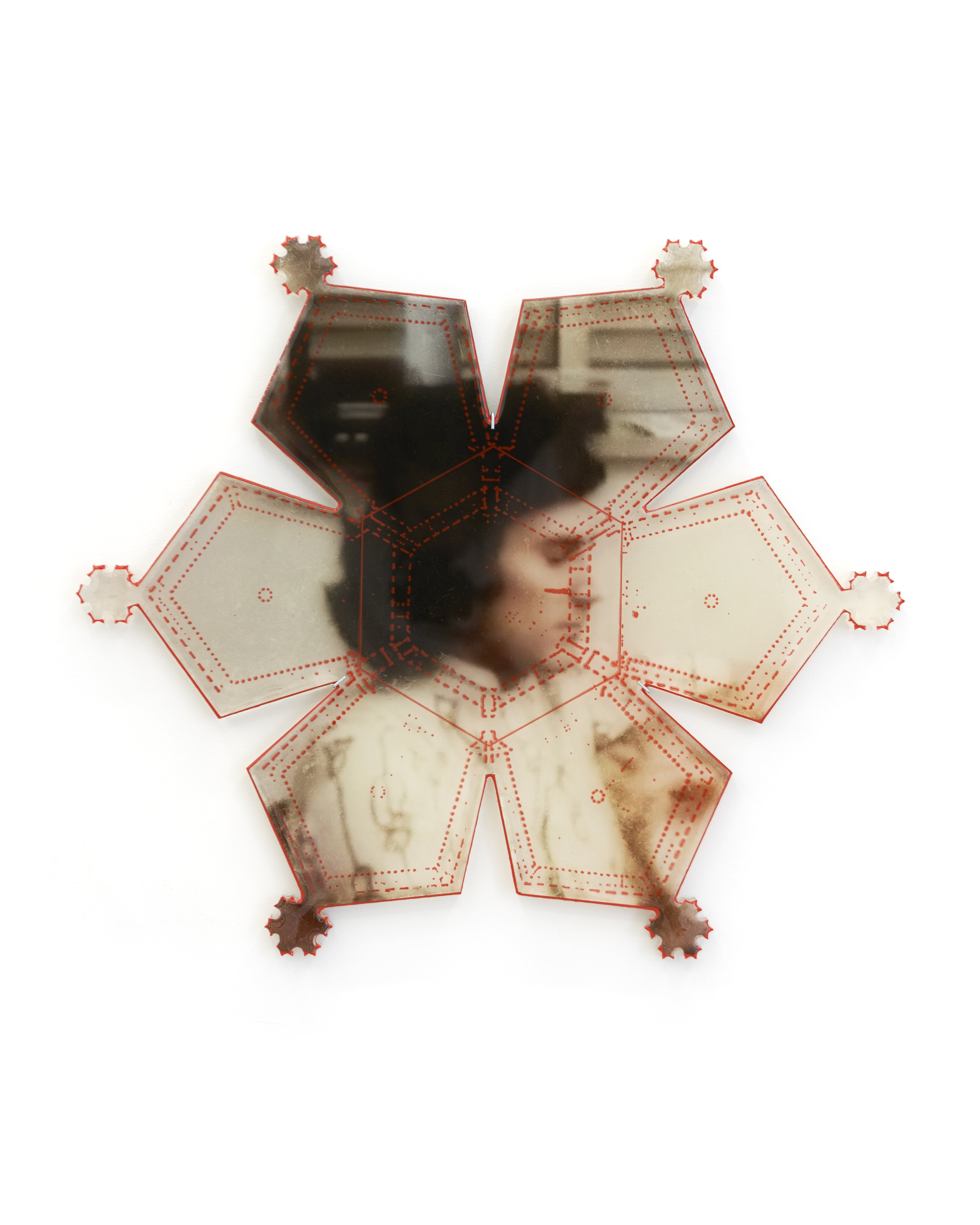

DARIUS AIRO: We talked about the idea of the mirrors being a way for me to enter the work physically or the environment, whether that's an actual individual who shares a public space with me or some graphic commercial thing. That’s kind of merging with me as an individual.

JON PYLYPCHUK: Josh [White] mentioned this idea of you glancing in a mirror every day and using that quick image of yourself as a partial reference in these works. Then, we talked about your walks through Chicago, absorbing the foliage in the earlier work, and then absorbing characters you see walking by and incorporating them in the new work. I was wondering if that mirror is actually just your subconscious reflecting all of these things. You absorb them, and then you reflect them for everyone else. But because they're not a perfect reflection, anybody can start applying who they see. You know, I see the person walking down a street in Altadena—they're like fixtures of this thing that only exists while I'm driving or walking by, they're almost like forms.

DARIUS AIRO: Not to depersonalize them, but yes, forms and color. Maybe it’s just the opposite of depersonalization—it’s putting them on a pedestal in the work. It’s about their personality or character. That’s a better way of thinking about it. I rely so much on this kind of intrinsic thing that drives the work—it’s so much about the viscera. And there’s something happening in the work that I have not a lot of say in but a lot of stake in, which makes the work inherently very personal. I can't and I don't necessarily want to step entirely out of the work, but I don't think I am ever engaging in this body of work as a self-portrait. I'm just very willing to embrace that I'm there. Do you get that?

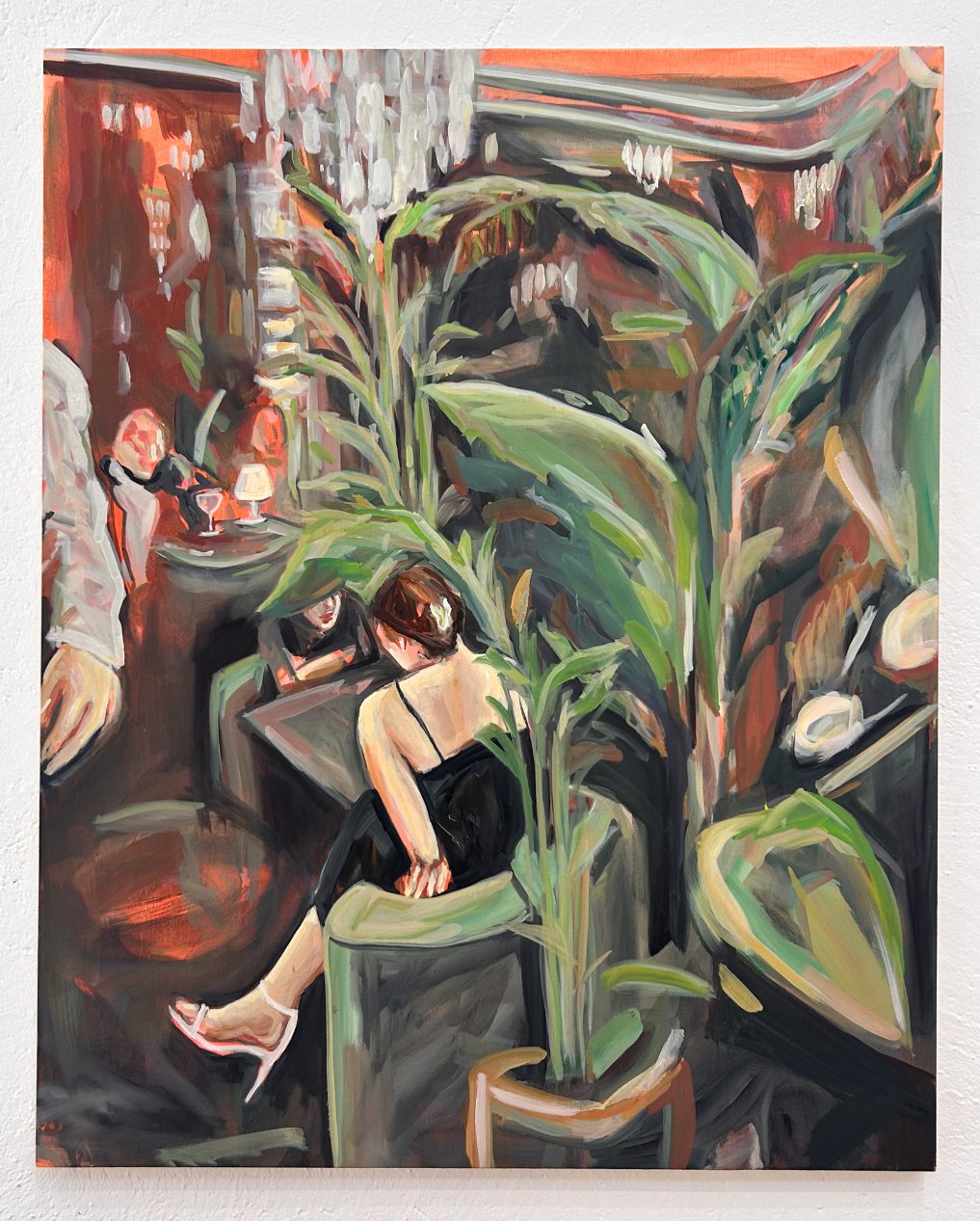

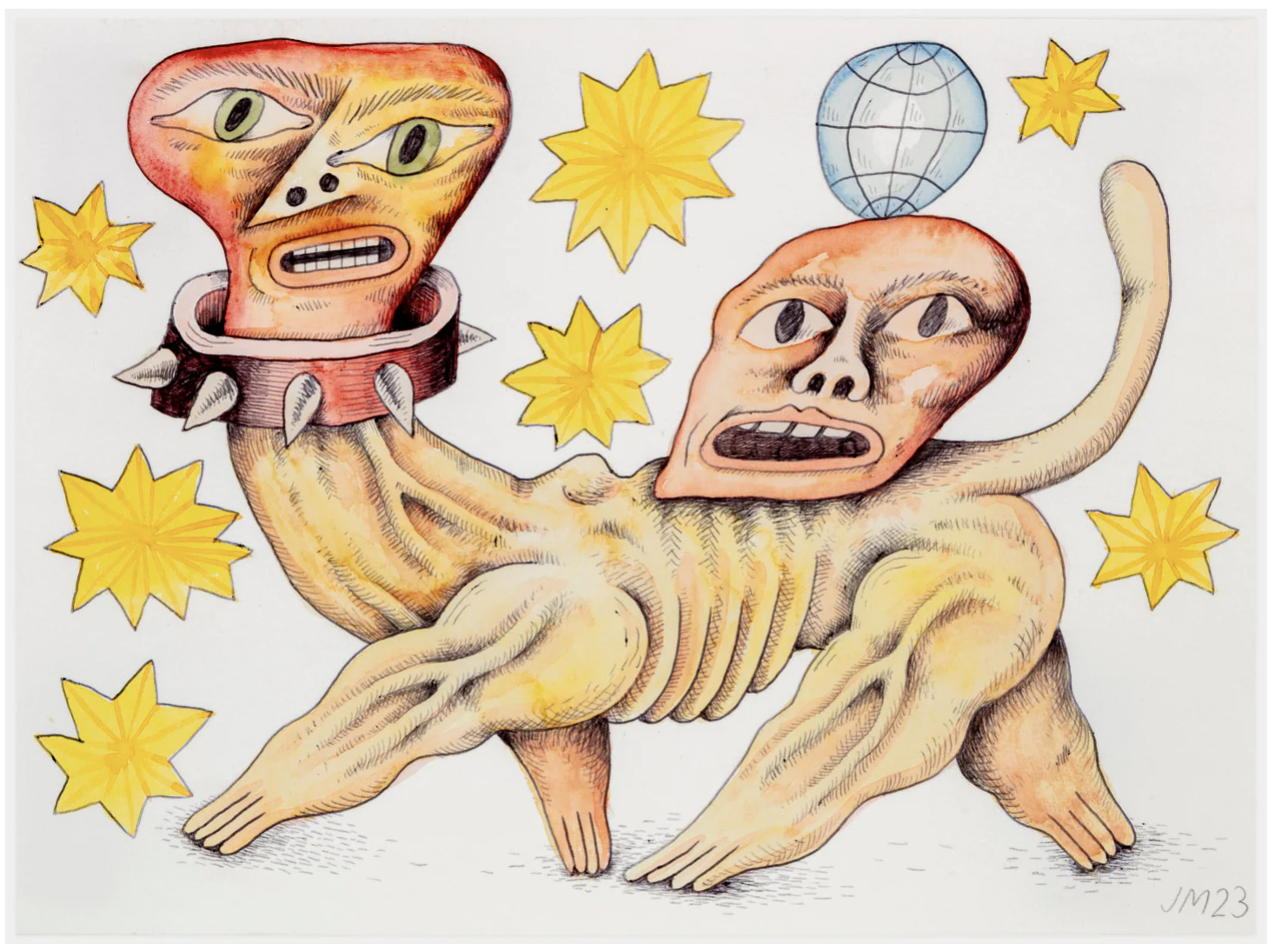

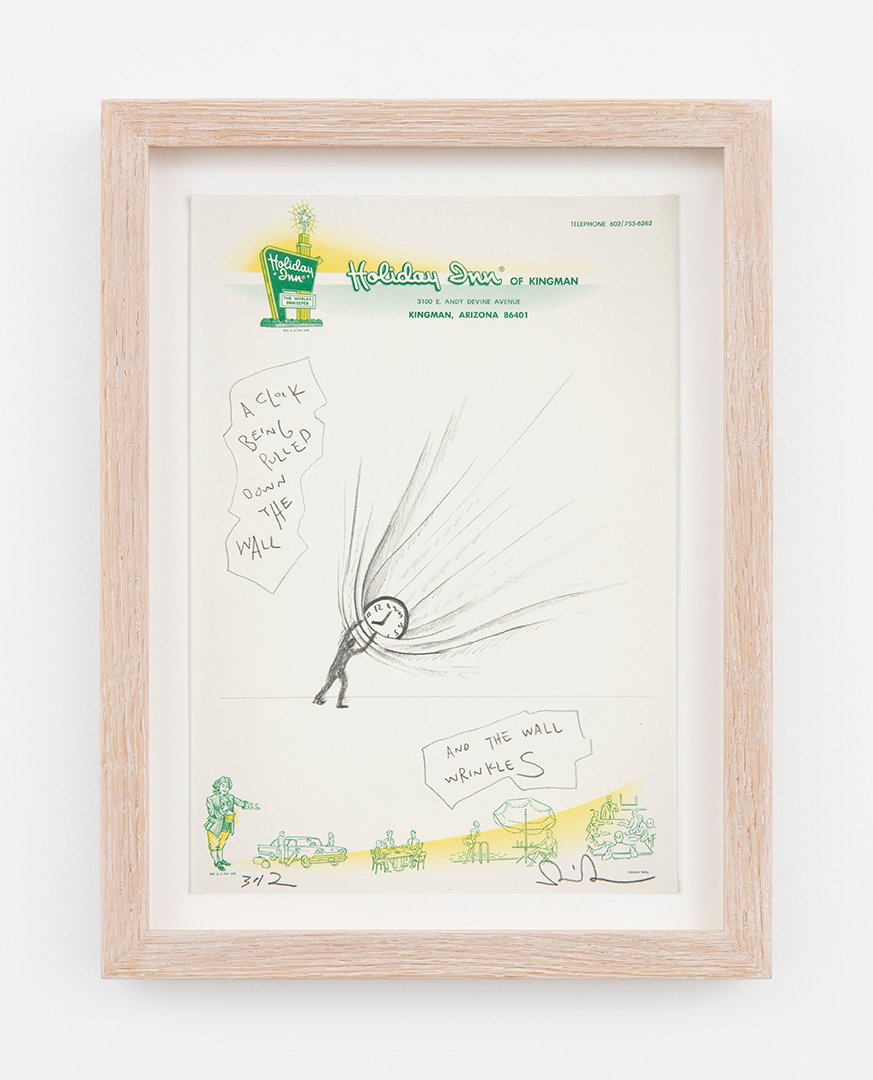

JON PYLYPCHUK: You know, when you just said self-portrait, it made me think of Cindy Sherman—making yourself up into all these people that you've seen on the street. And because your perception or visualization of these people is incomplete, you are actually just drawing yourself. Rather than being a self-portrait, it's a portrait of those people through you. And because they're incomplete, your mind is waking them up, and you're allowing the confidence and strength to just let your arms do what they're supposed to do. When I think about the things that I've done, the individual characters were almost irrelevant to the idea of how they were interacting with one another. In your case, it's the depiction of the character; in my case, it was always the depiction of the action. The words really were the most important part because anybody could sort of apply who's talking to who, but really, it's what they're saying to one another that ends up being the reflection to me.

DARIUS AIRO: That’s very interesting, what you just said about it not being the characteristics, but about the words, and that is how people can step into them. Because you can recognize the guy walking down the street in LA or Chicago, Your work is almost like statues or monoliths dedicated to those people.

JON PYLYPCHUK: The more I engage with them, the more I'm starting to see that. Whereas I don't think that I saw it at first. I saw 'em sort of as portraits, but now I'm starting to see aspects of the narrative coming through. And that narrative might not have been generated. It might not even be something that you were thinking about, but because they have this open nature, I'm gonna start applying that. And I think that's a really good indicator of strong work. You're giving people enough information so that they can decide what they see, and you're not telling them what they see.

DARIUS AIRO: Well, I'm figuring it out, too. (laughs) I'm kind of piecing together who, what, or when is stamped onto these images after the fact because they're so immediate and speedy—maybe not far from thoughtless or meticulous.

JON PYLYPCHUK: I really don't think that thoughtlessness is a bad thing because that place where you realize that you just did ten things and you don't even remember doing them, that subconscious flow state of creation, is the greatest place ever to exist.

"my own personal sun" 39x25.5in chalk pastel on paper 2024

DARIUS AIRO: I just read this book of Philip Guston interviews and writings called I Paint What I Want to See, and he's talking to Morton Feldman about how he wants to be a victim. And Feldman says he longs to be the victim of a sublime executioner. (laughs)

JON PYLYPCHUK Now that you mention Guston, it made me start reevaluating my thought that you were actually the love child of Joyce Pensato and ‘90s Karel Appel. Maybe there was a three-way, and Guston was in there somehow. Or maybe it was an immaculate conception. There’s a feeling in the hand of Pensato—the facility with the materials, and then this incredible sense of color that I don't see very often but that I remember in these ’90s paintings by Karel Appel.

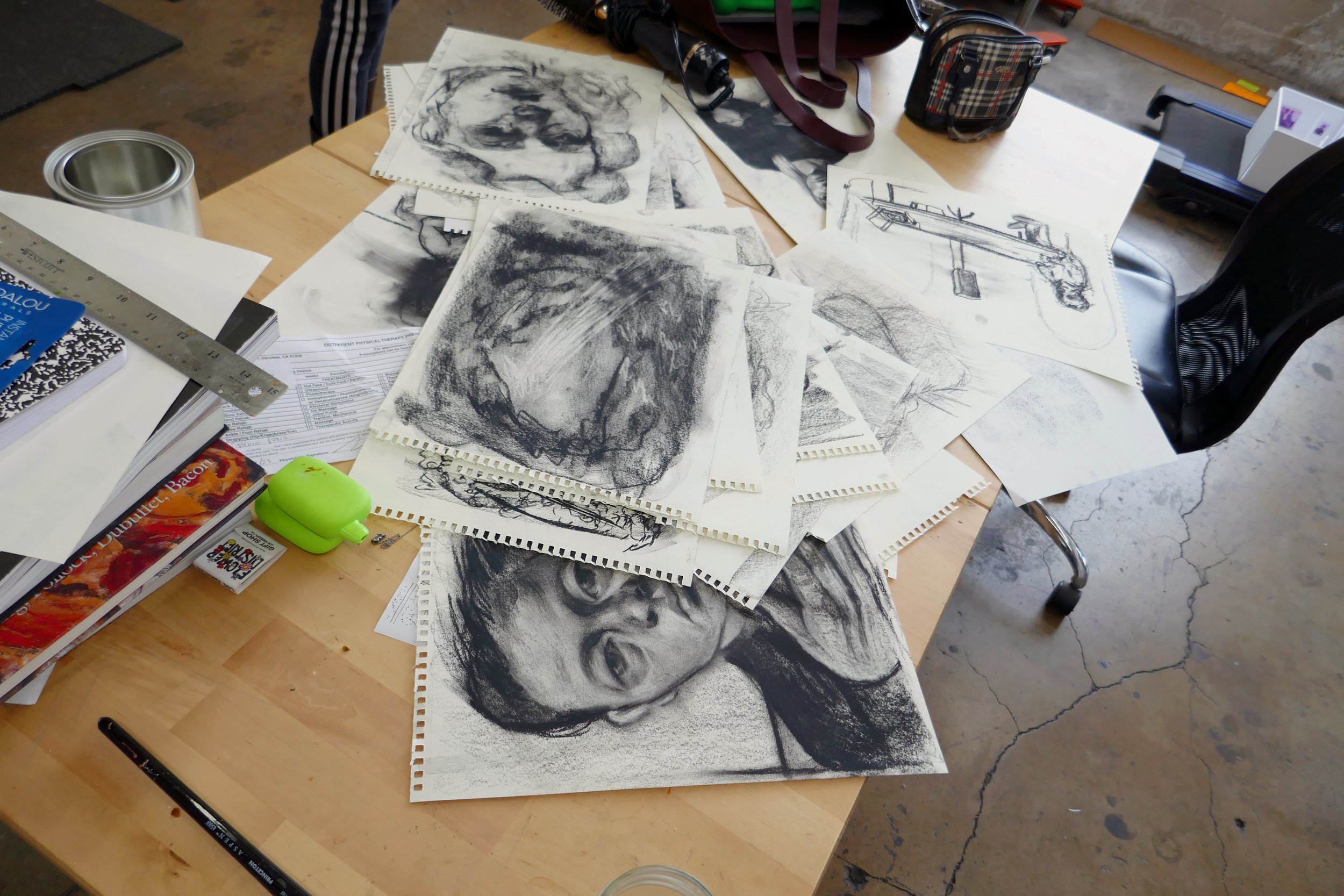

DARIUS AIRO: We discussed pastels being this immediate line and lacking fussiness. You have your color made, and you have the line that you're going to make with the edge of the material. So, it's very speedy and kind of shrinks the space between your brain and your hand. Whereas with oil painting, or anything that's a little more involved, it can be so fussy. There's a lot of laboring over the preparation, or you’re immediately thrown into this negotiation with art history. Do you feel that too?

JON PYLYPCHUK: Yeah, definitely. You're in your underwear when you use pastels. When you're painting, you have to sort of plan how your day goes and button up. It’s like the difference between shooting somebody or stabbing somebody; the immediacy of the pastels is that stabbing feeling. There’s such direct contact with the paper. The materials I've used have generally been left strewn about the floor. I’d be lying on the floor, and whatever I could reach, I could use. It changed over time with making larger-scale works, but there was always poetry in using shitty materials to make something poignant because, in a lot of cases, the words were the most important part. I would definitely use things like pastels in some situations if they were necessary, but I'm a little bit more of a blunt-force instrument as far as materials are concerned. I don't have that facility with pastels the way you do. I can draw pretty good lines here and there, but it's almost easier for me to turn something into something. I'll find a scrap of something on the floor that looks like something, and I'll go, oh, that's a cat's head, and I’ll use that as a cat. It was almost ready-made in that somebody wiped their mouth with it and threw it on the ground. They built that form for me, and I used that form to depict whatever character I needed to depict that form.

DARIUS AIRO: That's interesting. I'm charged by the same kind of stuff lying around that grabs you for whatever reason, but there's a filter between the objects. I'm not using ready-mades, but I'm certainly inspired by the objects that I find all the time. They’re just different ways to get to the same place.

JON PYLYPCHUK: I read [Terry] Myers's essay in the book for your exhibition where he quotes de Kooning, who said, “Everything's a face. And if everything's a face, then you have an endless supply to draw from.”

DARIUS AIRO: Right. It took some people, Terry, amongst some other folks, to keep mentioning de Kooning to me. And I love ’40s/’50s de Kooning, obviously, but I didn't recognize the relationship to these works until after people started bringing them in. It's interesting talking about the isolation that happens in the studio in a place like Chicago. You’re making all this work and then finding months later, oh yeah, de Kooning was in here.

JON PYLYPCHUK: Yeah, we had a similar climate with minimal natural light during the winter in Winnipeg. Often, people describe Winnipeg as the Chicago of the North. You'll go out and do one thing and then come back, and three days later, you're finished doing what you're doing in the studio because that's all you do. Because it's cold and it's dark at 3:30 PM. So, you start building a narrative for a group of characters that you are maintaining as contact. And if you're seeing them in this mirror you're passing every day, that's your mind going, okay, it's time to talk. I imagine there's probably a longitudinal line of parallel existence for people who all live above that point where it's dark at four o'clock in the afternoon.

DARIUS AIRO: It’s inherent to the process of the work where there's this trance-like thing where the work just kind of happens, and you're being guided by the sublime execution, and there's only so much you can do to detach from the things that you're interested in, and whether it's environmental or it's the beloved art history that seeps its way into everything, rather than trying to make a painting that looks like a ’50s de Kooning, you’re making a painting and recognizing what it is about these moments in art history that you feel connected to.

JON PYLYPCHUK: The history probably exists within your mind, and you have the opportunity every once in a while to have that subconscious guide your hand. I'm still trying to understand whether I think that jazz improvisation and that space are the same thing. You're relying on the knowledge of art history as a musician, which relies on the knowledge of music theory and a certain facility with the instrument. As a visual artist, you're relying on a facility with your materials, and then the rest is left up to who-knows-what to actually manifest.

DARIUS AIRO: That makes sense. I think I listened to ten different genres of music while making this body of work. And lots of silence, too. What do you do?

JON PYLYPCHUK: That's not me at all. Sometimes, it's just like the same song over and over again on repeat for three or four hours. Or for like a month at a time listening to the same song. I started doing that around 2015 as a portal. Your brain follows the music, and the rest of everything shuts off, and then you can start making work. I used to lay on the carpet and make drawings and listen to music and listen to full albums at a time. And a lot of the text that was in that work came out of lyrics that I heard. I would write something down, and then I would check the lyrics to make sure that I wasn't plagiarizing. But it's interesting what the brain hears when it wants to hear, or if the brain is in a certain trajectory of like interactions between two characters on a page, and then all of a sudden, you hear different lyrics, and then you look at the lyrics, and you're like, wow, that's totally not what that was. But you heard what you needed to hear to write down.

DARIUS AIRO: In one of the books of drawings that I made. I wrote a lyric from the Stones’ song “Moonlight Mile” that says, “I'm just living to be lying by your side.” But I heard it as, “I’m just living to be dying by your side.” It's much more bleak, but I like what you said because I can embrace it as my version and let that be okay.

JON PYLYPCHUK: As I understand the visual things, you see about 5% of your visual frame in 20/20. Your eyes are constantly scanning, and then they send that information to your brain, and your brain makes up the rest. So, I think it probably also happens with your ears, and your brain just tells you that that's what happened. You heard it that way because, at that point in time, you needed to hear it that way.

Mickey’s Mirror will be open from May 25 with a vernissage from 6 - 8:30pm