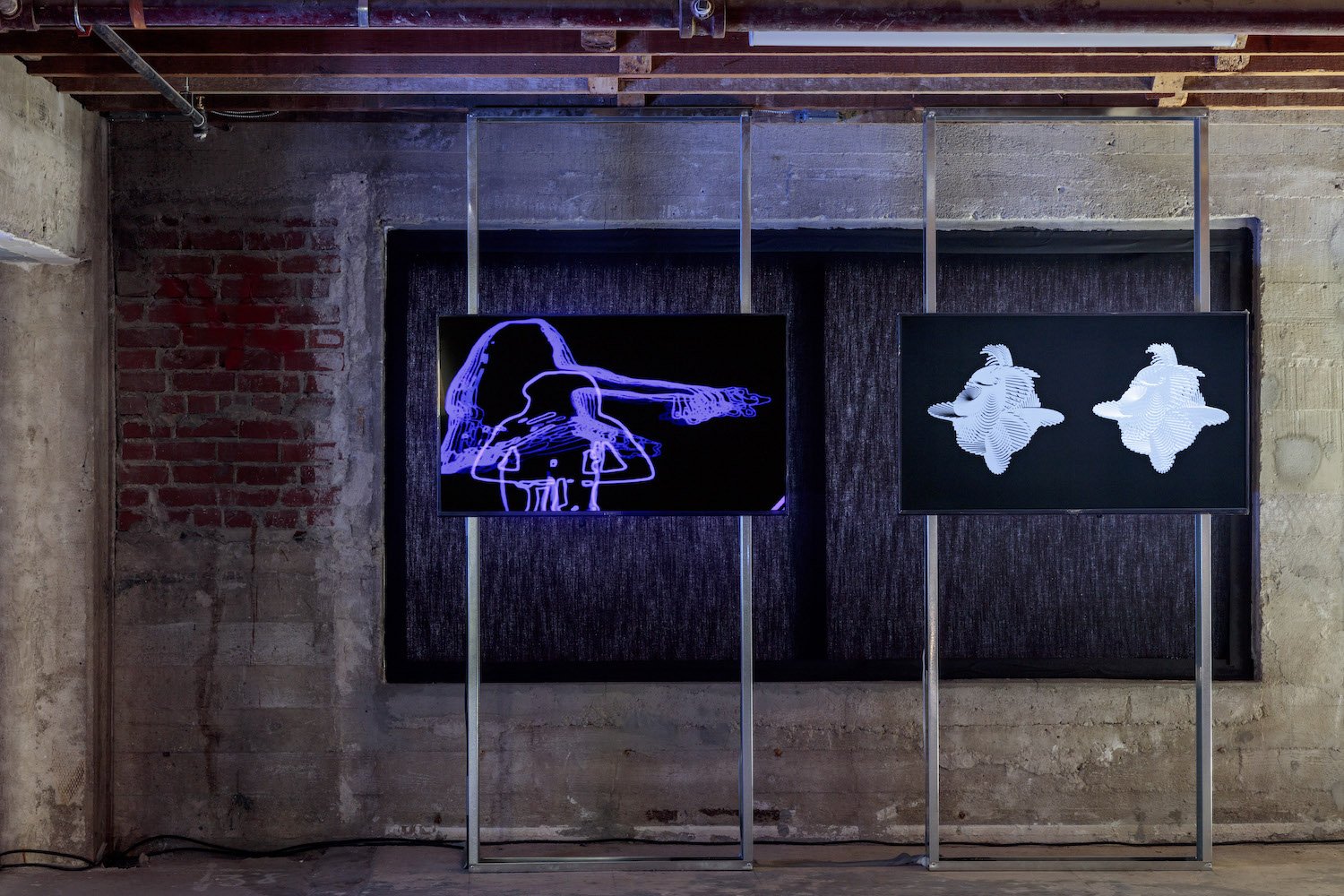

Annie Sprinkle "Bosom Ballet" 1990-91, courtesy the artist

interview by Mieke Marple

From the auction house to the titty bar, the art fair to the witches’ retreat, Sarah Thornton has moved her ethnographic eye from the art world to the titty world—and we are all better for it. Tits Up: What Sex Workers, Milk Bankers, Plastic Surgeons, Bra Designers, and Witches Tell Us about Breasts explores what breasts mean to five different breast-experts. The result is an ambitious collage of uplifting sagas (also the original name for Thornton’s book before the publisher asked her to change it). Thornton and I met over Zoom to talk about some of these lived experiences, particularly her own—everything from what inspired her to write the book in the first place to how writing it changed her relationship to her own body.

MIEKE MARPLE: How are you doing?

SARAH THORNTON: I’m excited. I worked hard on Tits Up and I care deeply about its content and mission. I’m keen on a broad readership. I don't want to just preach to the converted. Yes, it's a feminist book, but it’s also critical of the women's movement’s general disregard of breasts. While researching breasts from different grounded locations — a strip club, a human milk bank, an operating room, a bra design studio, and a pagan witches’ retreat in the redwoods — I realized that each of these social milieux raised issues of historic discomfort to mainstream feminism. The American women’s movement has generally not embraced sex workers, breastfeeding, or beautification, and definitely not plastic surgery. It has historically had a negative relationship to fashion and has been embarrassed by feminist spirituality.

It feels good to grapple with an elemental body part. All humans have nipples and most of us have a relationship to breasts. But Tits Up is full of surprising information. I hope Tits Up is useful for conscious-raising.

MARPLE: You told me that Tits Up is the best thing you've ever written. How do you know that? Or when did you know that?

THORNTON: I love researching. Every time I write a book, it's like completing another PhD. This is my fourth book and it took me six years. During that time, I had the benefit of twenty-three student apprentices because I was a scholar-in-residence at the University of California, Berkeley. Their library research allowed me to be even more ambitious for the ethnographic part or primary research of the book.

I also think I'm getting better as a writer. My voice is pretty distinct. It's mine. I'm not apologetic. So, it’s my best book because of the depth of the research and my greater facility at conveying insights in entertaining ways.

MARPLE: When did you know that this was the book you had to write?

THORNTON: Well, um, I didn't initially know it was a book. I started off by writing an article called “A Brief History of My Boobs.” It then became a therapeutic preamble to a deeper investigation as well as a position statement and declaration of purpose. When you write about a body part, you need to be honest and clear to both your interviewees and your readers about where you're coming from. Then, I started reading everything I could get my hands on. I have bookshelves full of breast-related books, body books, and feminist books. Then, there were hundreds of academic articles, usually very siloed in terms of discipline. But there was not much written that joined it up together.

MARPLE: No holistic view.

THORNTON: Exactly. So, after reading everything I could get my hands on, I realized nobody had written the book that I would write. I realized there was very little about contemporary breasts, especially the in-person real world of living bodies. I've taught media studies, but living breathing experiences (rather than virtual ones) are what give me a buzz. I realized that nobody had done what I felt I could do. And I knew I could do it because I’d written Seven Days in the Art World. I understood early on that a kaleidoscopic perspective on breasts could be rendered as an engaging five days in the titty world.

Chitra Ganesh "Black Vitruvian Tiger", courtesy the artist

MARPLE: How did you choose those five worlds? And what were some of the other ones you considered?

THORNTON: I started out by interviewing between fifty and seventy possible experts. I interviewed all sorts of people like ballet dancers, breast cancer survivors, gynecologists, feminists, all sorts. And what hit me over the head were five clusters of people who were saying things that I had not heard before — things that blew my mind.

MARPLE: Because they have been largely marginalized from mainstream feminism?

THORNTON: Yes, absolutely. They were the people who had the most interesting things to say about breasts. The number five was not a specific choice. It was just the number of worlds that came up as relevant to the story of breasts in America today. I didn't see another social world or boob environment that I needed to examine in the same way as these ones.

MARPLE: Is there any significance to the order of the worlds, starting with the strip club and ending with the witches’ retreat?

THORNTON: I moved from dominant perceptions of breasts to more obscure ones. The dominant view of breasts in America is that they are erotic playthings. I thought, okay, I'm going to start there, but I'm going to look at it from the sex professional's point of view. The women who make a living from breasts as erotic objects. The second prevailing association, because most women become mothers, is breastfeeding. Even women who don't breastfeed will have had the experience of their boobs get big when they’re pregnant as they prepare to breastfeed and their milk comes in. The most obscure niche culture is the nature-worshiping neo-pagans that came out of the hippie movement. So, the chapters move from perceptions of breasts that are mainstream through to a very small subculture, but the religions I touch on in that chapter are huge: Judaism, Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism. So, I intersperse the very specific with a pretty grand historical narrative.

Loie Hollowell "Milk Fountain," 2020-21, courtesy the artist

MARPLE: And at the witches’ retreat? Was it mostly older people?

THORNTON: Yes! The other trajectory is from young to old because age is super important for the life of our chests. The youngest interviewees are in chapter one, “Hardworking Tits.” Sex work skews young. Then, comes “Lifesaving Jugs,” and motherhood. Between postpartum and menopause, a massive number of breast surgeries happen. Chapter 3, “Treasured Chests,” discusses all the “Mommy Makeovers,” the lifts, trans surgeries, and the plastic surgeries that women have after cancer. The bra chapter, “Active Apexes,” named for the apparel industry term for nipples, is for all ages, but then “Holy Mammaries” focuses on the crones. So, yes, the lifecycle is part of the chapter sequence.

MARPLE: Interesting how the dominant view intersects with youth and the most obscure intersects with age, though that is where the most collective wisdom and grandest insights lay. Of course, that mirrors societal attitudes towards women and the devaluing of them as they get older. Still, I appreciate the youth-to-old-age life span in Tits Up. It gives the book this subtle, epic narrative quality.

THORNTON: Thank you. I aspire to epic.

MARPLE: So, how did writing the book change you?

THORNTON: Oh, my god. Well, I feel much happier in my body. I actually feel transformed by the experience of researching and writing the book. All of my characters’ experiences and insights have enlightened me and uplifted me. I feel less stressed and shamed by my fake boobs and my aging. I still lament the loss of my original, natural breasts. But then, losing them led me to write a book that I'm really proud of, which I would never have written.

MARPLE: Why not?

THORNTON: I don't think I would have felt like I had the authority. In writing “A Brief History of My Boobs” which appears in the book’s introduction in an abbreviated form as “Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder,” I was like, you know, the gals have chalked up quite a bit of experience. They’ve never done sex work, but they’ve understood from the inside a lot of important narratives – budding womanhood, sexual harassment, breastfeeding, cancer scares, amputation, and reconstruction. Then, I did all the reading, and interviewed over two hundred people, and did all of that on ethnographic on-site fieldwork. So, I'm not a doctor. I don't have the obvious credentials about “breasts,” but I have gathered, synthesized, and thought hard about many women’s perspectives. I know a hell of a lot about tits, jugs, chests, racks, and knockers.

photograph by Aya Brackett